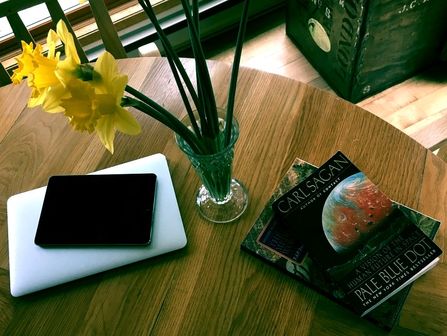

One debate in education is brought to my attention more frequently and more fiercely than most others: to what extent technology should dominate our classrooms. Most recently, I heard it between teachers at a workshop on iPads in the classroom. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the heavily voiced opinion was that technology – and iPads in particular – was king, and that non-technological methods – textbooks in particular – were categorically useless. Despite my dismay, I understand how we got here. Technology seems to divide teachers into two camps; there are those who feel that digital learning tools will make everything better, and those who have greater reservations, but who come under increasing pressure from the first group. That our students need to be educated about technology has become unavoidable, but being educated about technology also means acknowledging its limitations. It means acknowledging other ways of learning, including textbooks. A common reason for schools to avoid textbooks is the notion that the information in them becomes “out of date” and will need to be quickly replaced. Schools are shying away from buying textbooks for the same reason that many of us don't buy news media anymore: it's expensive, and we're under the illusion that we can get the same thing on the internet. This is a fair concern, but realistically, how does this compare to technology? Let's assume that textbooks need to be replaced every ten years in order to be accurate. Is it likely that a class set of iPads or laptops will make it that long in an elementary school, which the everyday wear-and-tear that they take? Experience suggests to me that they won't. Aside from cost, though, there is a difference in quality between paid and unpaid material. Though there are great sites and sources that will give away information for free, many websites simply do not do the same job as a textbook. Textbooks are expensive for a reason; they are, when done properly, carefully curated information presented for a particular audience – in this case, adolescent learners. They have been written by somebody who has had to put their name on the information. They are, as much as a single source can be, a reliable source. In some cases, these strange old fashioned tomes can yield an unexpected picture of the past. In my classroom, I keep a set of “Time Life Great Ages of Man” books. They were written in the 1960s and 70s, and they each detail a different period of world history. They aren't the friendliest looking books from the outside, but inside, they are fluidly written, and contain beautiful photo collections at the end of each chapter. One of my students was reading the book about the 1700s, and ask me why, in the introduction, the author commented on the fact that in his time, men were “trying to destroy the world.” I explained to her in broad terms the concept of the Cold War, which would have been relevant at the time the author was writing. Critics of textbooks would point to this as another example of how textbooks are archaic and useless; I see it as a chance to talk about authorial voice and bias, and the context in which history is written. These are issues and skills that are no less relevant to the modern digital user than they were generations ago; if anything, it is more important than ever that students have a base of information from which to make judgements. One critical skill in technology education is evaluating sources for their reliability, but in order to do that, you need to know things to begin with. Simply throwing students onto the internet to teach them “media literacy” is naïve, if that media isn't compared to something. Far from being inferior to digital media, textbooks and print media still provide a perspective that an internet search does not. They give us a glimpse into a moment in time and the author’s thoughts on it, and hopefully allow us to be inspired in our current moment by the writing of the past. As an example, Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot is arguably scientifically obsolete; it was published over twenty years ago, and it will not give you an up-to-the-minute account of space travel. What it will give you is inspiration and vision, and the perspective of someone who understood that knowledge is ever-changing, so long as we pursue it. Sagan’s book is full of hope, that instead of turning down a path of ignorance, we will look together to planets of our Solar System, and find a way to reach them. That our knowledge has progressed beyond what Sagan knew does not make him wrong; hopefully, it makes him right.

0 Comments

This week... I have something a little different. It is a song called "The Clearest Lens" (lyrics below). It's about how we see our world and our universe differently through the eyes of those we love. As always, it's for my husband, Patrick. Happy Valentine's Day. Enjoy. The Clearest Lens (Going to the Stars)

Music and Lyrics by: Jane Perrella You tell me that to see the past I only need my eyes Open them to ancient light that soars across the skies You trace the shapes of space and time in one black sweeping arc So grab your coat, turn out the lights, we’ll see better in the dark Let me follow in your footsteps far across the Milky Way Show me nebulas and galaxies invisible by day Your love is the clearest lens that I will ever know If you’re going to the stars, take me with you when you go. When the wonders of galaxies are too far away to see You search the skies with binoculars before giving them to me And when I find that speck of pale light I can hear you say “There’s Andromeda, our neighbour, two million light-years away” Let me follow in your footsteps far across the Milky Way Show me nebulas and galaxies invisible by day Your love is the clearest lens that I will ever know If you’re going to the stars, take me with you when you go. I shivered while you tinkered with our telescope that night, Until you show me where to look and I found in my sight The Orion nebula’s silver stars lighting up the skies The universe is brighter when I see it through your eyes. Let me follow in your footsteps far across the Milky Way Show me nebulas and galaxies invisible by day Your love is the clearest lens that I will ever know If you’re going to the stars, take me with you when you go. I won’t deny that in thinking of content for this blog, my mind wanders to the maelstrom that is the current political climate. I could say that I have made a conscience choice not to add my own noise to this political tempest – that would even be partially true. But it would truer still to say that every post I have made has been political on some level. Education, science, technology, reading and writing: these are all political acts, and always have been. Nowhere is this truer than in books.

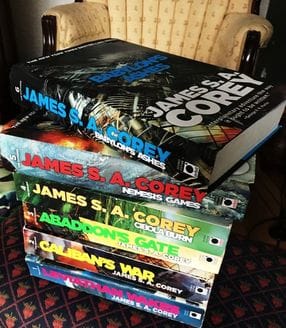

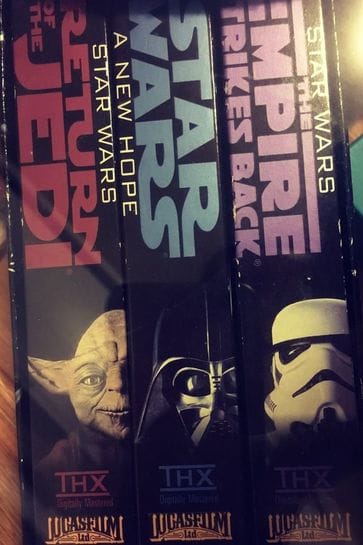

This week, while following the writing team of James S.A. Corey on Twitter, I saw a tweet in which someone – apparently a fan – urged Corey in no uncertain terms to stick to writing fiction and leave political criticism alone. This is laughable. The idea that a writer could convey more political upheaval in a 140 character tweet than in six novels is absurd. It would be absurd even if the novels of The Expanse (Corey’s scientifically fabulous space opera) did not demonstrate the empathy and political depth that they do. It also made me laugh, to think of what James Holden of The Expanse would do if he were told not to tweet about politics. I’m thinking he would retweet everything, all in caps. Of course writers can, and probably should, comment on the politics unfolding around us. In a way, though, they almost don’t need to – they have already done so in their books. The books we choose to read, write, and criticize are our voices; that they do not speak directly about current events does not diminish their political significance. My students presented their Classic book projects this week, and had to answer the question “is this book applicable today?” With books including Lowry’s The Giver, Wells’ The War of the Worlds, and Huxley’s Brave New World, the applicability was painfully obvious. Books do not need to feature oppressive dystopian regimes to be acts of politics. They are political acts because they teach us empathy; they teach us how to analyze and understand villainy and corruption, how to forgive those who have done wrong, how to feel compassion for those who have suffered. They teach us to care about people who we have never and will never meet; they are a reminder that when we look out at the world, the stories of strangers are worth hearing. If that is the role of books, then what is the role of writers? We don’t need to blog about current events or create fictional statesmen in order to write politically. There are no statesmen in my novel, The Steel Lady: only 19th century engineers, factory workers, and women. Writing of their struggles not only gives empathy to their fictional lives; it lays bare conflict which the 21st century has not left behind, such as ignorance, fear of progress, and sexism. It would be narcissistic of me to claim that writers are somehow uniquely qualified to give political commentary, but to suggest that they should stay in their fictional worlds is to miss the purpose for which those worlds were created. Books have never been apolitical - why should writers be?  I recently recommended Marissa Meyer’s new book, Heartless, to one of my students, who became as riveted to it as I had been. I asked her what she thought of it as she was reading it, and she called it a “roller-coaster.” Indeed. (Mild spoilers ahead.) Heartless is the origin story of the Queen of Hearts. It’s the story of Catherine in the land of Hearts, and her official courtship with the King of Hearts, as well as her love story with Jest, the dark and dashing court joker. This being Wonderland, there are twists and turns aplenty, and delightful references to the source material from Lewis Carroll. There is so much right about Heartless, from its love story to its whimsical images to the feeling that the entire novel is one breathless night out. Ultimately, though, it remains the story of the creation of a villainess, which sooner or later involves trauma. Watching Catherine’s transformation into the Queen of Hearts is a bit like watching one of Jest’s magic tricks: the clues are all there. You already know the ending, but you don’t see how the trick is done, because you’re too caught up in the flourishes. You’re not really looking. Or at least, I certainly wasn’t. I was far too caught up in walking through the labyrinth of their story to see the shape of the entire thing, and I must insist that this is not the fault of the story. Arguably, it’s one of its strongest traits. It managed to jump an ending on me that I didn’t anticipate, but which was not undeserved. It strikes me after reading Heartless how difficult it is to offer an opinion of a book without its ending, when that is what decides our satisfaction with our reading experience. Was it, to put it simply, worth it? If I’m honest, every time I open a book, I more or less expect a happy ending. Perhaps that’s why the end of Heartless broke my own heart a little. It was good storytelling, but it left me with the sense that there was no way out; for Catherine and Jest, the choices they make seem to be no match for forces like Fate and Chance. And yes, I know, life is rather like that; the good suffer just as much as the bad. In real life there is no ending, just a rolling series of unfair and unrelated events. I enjoyed Heartless, and would still recommend it on the grounds that it makes much of its material. I will add, though, that if you like your heroes and princesses to be more-or-less intact by the end of the novel, I would go for Marissa Meyer’s Lunar Chronicles instead, starting with Cinder. Less of a roller-coaster, but still a great ride.  I have been shying away from writing a review of Rogue One, because it seems to me to be impossible to do so without spoiling it. So instead, I’m going to write a review of the reviews of Rogue One; specifically, I’m going to take issue with the use of the phrase “It’s for the fans.” Whether the writer of the review is a fan or a critic of fans, the use of this term strikes me as sloppy. If the writer is a fan, it is a dismissal of criticism; it gives the fan permission to ignore the potential flaws of the work in question. If the writer is a critic, the phrase “it’s for the fans” is a dismissal of value; it gives the critic permission to ignore the achievements of the work in question, on the basis that they are an outsider, who doesn’t get it. I can understand the use of this term in reference to The Force Awakens. Much as I enjoyed it, the main gambit of The Force Awakens was nostalgia; it relied heavily on the fact that its viewers had seen, and adored, the previous three movies in the series, and were anxious to see more of them. In fairness to The Force Awakens, it delivered; Star Wars fans can be notoriously difficult to please, and apparently what they (and we) wanted was in fact a movie almost exactly like the originals, but with a promise for more. This isn’t true of Rogue One. I can only speak from the perspective of a long-time fan, but it seems to me that it would be equally valid to see Rogue One before seeing A New Hope, as the other way around. A central reason for this is the fact that the characters of Rogue One are as unfamiliar to fans as they are to viewers new to the franchise; Jyn Erso and Cassian Andor are not household names, as Skywalker and Organa and Solo are. In the course of a couple of hours, the protagonists of Rogue One need to earn the sympathy of the viewer from scratch. Calling Rogue One “for the fans” ignores the fact that they do earn it. It ignores the shared despair and hope and triumph and tragedy. It ignores that this movie goes beyond simple themes of good, evil, and redemption, and taps into more complex themes of what we are willing to do for liberty, and what we give up in order to get it. It ignores the fact that the Star Wars universe is vast and varied, and can provide more than just fairy tales with princesses and knights; it can also provide stories with grit, dark humour, and political awareness. For the Star Wars universe to grow, the old guard of Solos and Skywalkers is not enough. It has had to create new characters, and it has had to make its viewers care, and care deeply, in a short space of time. Despite its nostalgia, The Force Awakens had to accomplish this as much as Rogue One did. Rey and Poe and Finn needed to be worth cheering for, just as Jyn and Cassian needed to be. It wasn’t enough for it to be “for the fans.” It also had to be good. If you have not already, go see Rogue One. Not because it’s for the fans, but because it’s how fans are born.  Our stage, made ready for A Midsummer Night's Dream in 2014. Our stage, made ready for A Midsummer Night's Dream in 2014. When I’m not editing my novel, I edit Shakespeare. I am well past the point where I find this to be horrifying. Here is why. I have read, watched, acted in, studied, and taught a great deal of Shakespeare. I might once have thought that Shakespeare’s plays had to be studied in their entirety, but early on in my teaching career, I made the choice that I would rather have my students read a slightly abridged version of Shakespeare, than no Shakespeare at all. In my grade six and seven class, my students perform and study Shakespeare in Drama every year. It started out as one play a year; through popular demand, it became two. Bringing Shakespeare alive means performing it. One of my privileges as an elementary school teacher is that I teach all subject areas. This means that when my students learn Shakespeare, they don’t just read his work, or listen to me talk about his world; they push back the desks and jump on the countertops and wield swords made of cardboard. And it works. They get it. Shakespeare may seem inaccessible to a twelve-year-old at first glance, but it’s full of drama, anger, love, mistakes, and people stabbing each other. It’s basically Young Adult fiction written in iambic pentameter. Performing the plays has required me to make certain decisions and modifications to the works that I use. At the moment, the three plays that I have edited are A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Richard III, and Julius Caesar. I know – Julius Caesar and Richard III seem like slightly odd choices, but aside from Drama, they also fit well into the grade six and seven Social Studies curriculum of Ancient Rome and the Middle Ages. More importantly, they and A Midsummer Night’s Dream share something in common: they all have last casts, and enough roles for all my students. Once I’ve selected the plays, I look at the existing language. I don’t change it into modern English; that would defeat the point of reading it. I simply shorten it. This is generally true of performed plays as well; generally, some form of editing has taken place, and this is for the most part a good idea. Hamlet in its full form in about a four-hour performance; the only person intense enough to do that is Kenneth Branagh, who of course did. For most performers and viewers, an approach like that taken by the producers of The Hollow Crown is more appropriate; they focused on the scenes that convey the themes they wished to highlight, and removed the rest. My final piece of editing involves me adding something instead of removing it. In tackling history plays like Julius Caesar, it became obvious that some background information was needed, and so I created Raj and Ky. Raj and Ky are time-travelling students, who travel in time to observe and comment on the events of the plays (for an excerpt of them as a Prologue to Richard III, see the block quote insert). It may seem a bit cheesy, but again, it works. With a little bit of information to start with, my students memorize and perform the plays, sympathize with the characters, and come to understand Shakespeare’s work from the inside out. Best of all, this access to Shakespeare stays not only with them, but with their friends and with the classes in the school who see the performances. Shakespeare is no longer something on a page; it’s something alive, powerful and relevant, an experience to be desired, and in some cases, demanded. On the first day back to school this year, one of my grade seven students, who had been in my class the previous year, walked into my room and said, “When do we start Shakespeare?” Right away. Ky: Let me check the date…. Oh.  You must read James S. A. Corey’s Babylon’s Ashes, the sixth book in the epic series, The Expanse. Actually, no, you must first read the first five books, and then read Babylon’s Ashes. You must do this, because of its utterly perfect narration. (Spoiler Alert: Just a teensy one. It doesn't ruin the story, but if you want to know nothing of Babylon's Ashes before reading, don't read the last paragraph.) There are many reasons why these books are worth a read, and even a reread: the setting of a near-future solar system colonized by humans, the breakneck and detailed plot, and the delightful characters, to name a few. But it’s important to note that the voices of the characters are clear and well defined because of the narration. Narrative style is critical to why The Expanse books engage so well and read so beautifully. The narrative style of The Expanse is crisp limited omniscience; we transfer between different narrators with different perspectives. Sometimes the narrators overlap in one scene, but generally not; we see some scenes from the perspective of one character, and some scenes from the other. The narration is tailored to the voice of the character who is speaking, even in so far as the metaphors that they use to describe their world, or the parts of life that they muse on. We are left in no doubt that there is a new person speaking. The narrating characters change from one book to the next. Sometimes they are foul-mouthed grandmother politicians, sometimes scientists and preachers, sometimes female Martian marines wearing power armour. Sometimes they are the villain, the antagonist speaking in their own voice. And running through all the books is the idealistic and charming narration of James Holden, captain of the Rocinante. (If you’re a Firefly fan and are missing Malcolm Reynolds, James Holden is a pretty amazing substitute.) Babylon’s Ashes, the latest installment, takes this narrative control to new extremes. Most of the books consist of four narrators – Babylon’s Ashes has about triple that. It should be a dizzying collections of perspectives, but it manages to not be because so many of them are old friends; we’ve met them before on previous missions, in previous adventures, and their narration manages to glide easily through the vast scope of this story. The storytelling of Babylon’s Ashes is most impressive when we hear the brief voices of those we have never met before. They seem inconsequential; they are bystanders, observers of mass conflict, a perspective that is neither the protagonist nor the antagonist. They are, of course, not inconsequential – they are exactly the point. Conflict on the scale of Babylon’s Ashes cannot be confined to the hero and the villain only; it ripples through their worlds and takes all human lives with it. There is a moment in Babylon’s Ashes when one character starts making videos of the lives of other people. He broadcasts them throughout the solar system, in an attempt to find some humanity and understanding in the midst of conflict. His action inspires others to make their own videos, to speak in their own voices. That is what the narration of Babylon’s Ashes is: the voices of humanity, in all their variety, telling one story.  VHS: my first Star Wars format, but not my last. VHS: my first Star Wars format, but not my last. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: this year marks the death of movies. No? How about the death of paper books? Of console video games? We have a strange and misplaced fascination with pronouncing the end of a particular media genre. As far as I can tell, we are generally bad at it. The articles lamenting (or hailing) the impending death of the movie demonstrate two interesting trends. The first is that movies as a medium will lose out to a new technology. The other suggestion is that the movie is “dead” because its content has become irrelevant and poorly thought out. Let’s address the technological one first. We have played this game before: movies will be the death of live theatre. Home video will be the death of movies. E-books will mean the death of paper books. All false. Yes, the market for consumption of these media forms has changed, but none of them have vanished. To suggest that they will fails to consider that they don’t do remotely the same thing. Movies can be amazing pieces of entertainment, but they do not provide the same experience, either for the actor or for the viewer, as live theatre does. The point is subtler but equally true of movies and television. Seeing a movie on a big screen is different than seeing it on a small one, and provides me with a different thrill than sitting on my couch; if it didn’t, I wouldn’t be lining up to see Rogue One in theatres. What about the replacement of home video rental for streaming services like Netflix, you say? Netflix didn’t replace a different medium; it replaced the same medium. The experience of watching a Netflix movie and watching a rented movie is not different. It’s just easier to get. We continue to hold onto a wide range of entertainment experiences, because they play on us in different ways. Live theatre is not inherently better than movies, just as movies are not inherently better than television; they are simply sufficiently different that they continue to hold onto their own domains of viewers. There are those who ignore the technological question, and lament instead that movies have fallen into a rut of producing terrible, lowest-common-denominator entertainment. The most glaring problem with this idea can be seen in comparison with another form of media: books. There are plenty of truly terrible books. Books that tell bad stories, or that tell good stories badly. Since the invention of the novel at the beginning of the 19th century, there have been piles of utterly terrible writing. The 19th century novel that you see reprinted today, the ones that we call “Classics,” are the good ones, selected over the course of time from amidst the waste of the terrible ones. In every format, it is possible to lack imagination and skill; it doesn’t destroy the format, it simply causes the bad examples of it to be forgotten. Movies aren’t dying, and movies as an industry are not the problem. Moviegoers can be selective with the movies that they see. Just as gamers can be with video games. Just as readers can be with books. Entertainment industries are shaped by their consumers, not the other way around. If you want quality stories, consume quality stories, in all their forms. That said, seeing a big explosive Hollywood blockbuster probably won’t do you any harm either. And it goes well with popcorn.  How do we define what is an art as opposed to what is a craft? As a grade seven teacher in BC, I teach both “Fine Arts” and “Applied Skills and Design,” and how I define these subjects makes a difference to how I teach them. I looked up the dictionary definition for both of these terms, and predictably, this made my question more complicated rather than less. Apparently, an art is “an expression or application of creative skill and imagination, especially through a visual medium,” while a craft is “an activity involving skill in making things by hand.” Even in the language used to define them, a craft is earthbound and everyday, while an art is high-flying, expressive and imaginative. It is interesting that so much of what we teach as Fine Arts actually starts with a craft. It has to start with the “skill in making things” whether it is ceramics, paintings, drama, music, or dance. Ceramics requires you to know how to work with clay, so that it doesn’t break; painting requires a knowledge of colour and form; drama starts with an understanding of movement and voice control; music is made of scales and chords and rhythm; and you have to learn the steps before you can dance. Crafts have so often and for so long taken second place to art, but it is a mistake to think that they are fully separate. Where they begin to diverge is in the “application of imagination,” and this is where teaching art becomes harder. Any Fine Arts curriculum has to, at some point, start marking students on their originality and creativity, but how do we make that happen? You can no more teach imagination than you can teach a plant to grow. You can give it an environment that is conducive to its growth, but by its very nature, imagination has to find its own path to the sunlight. The Applied Skills curriculum allows for a wide range of skills and crafts, and one of the units that I teach in my class is knitting. My students all get needles and yarn, and are taught basic skills, including how to knit and purl, and how to follow a pattern. This would seem to be a straightforward craft. No imagination is required; they simply have to learn the skills. Yet while some of them enjoy the satisfaction of learning those skills for their own sake, where they take them is not always something I can predict. One student made a piece of knitting that was, essentially, a mistake – she ended with far more stitches than she started, and instead of making a square, she made a sort of triangle. But instead of rejecting it as a failure, she sewed it around her hand into a wrist warmer. What she created was unplanned, an attractive and useful result of skills and imagination. For some students, painting seems impossible. Clay never works for them. Drawing is not their strength. The beauty of teaching a range of crafts is that they may find in it something that they can make into art. Alexander Calder, a 20th century artist who produced wire sculptures that he described as “drawing in space,” commented once “I think better in wire.” There is a place in art for those of us who think better in yarn.  A debate took place in my class yesterday, about whether spirituality or science was a more valid guiding principle – you know, just another day in a grade seven class. It went mostly as you would expect until one student, arguing for spirituality, insisted that those who only follow science are close-minded – that they can’t allow for other possibilities. This view fascinated me. It suggests that the student sees science as hard facts, lines drawn in the sand, rather than as a way of questioning and exploring. It should be exactly the opposite – the more questions that science asks, the more open-minded scientists have to be, as they become aware of how little they know. Perhaps this is less about how science actually operates, and more about how it is taught; it leads many people to see themselves as outsiders to science. Which is wrong, of course. No one is “outside of science,” or its consequences and applications. Our lives are lit, driven, organized, and entertained by applied sciences. None of us is immune from the laws of physics, though they may as well be magic for all most of us understand of them. Unlike our ignorance with computers, our dismissal of science is not new. Over fifty years ago, C. P. Snow wrote “The Two Cultures”; he argued that the gulf between scientists and “non-scientists” (in this case, literary academics) was so wide that they were unable to understand, and even tolerate, each other. “The Two Cultures” shows its age; it can be elitist in its ideas about education, and it makes frequent references to the Cold War. For all that, it remains surprisingly relevant. Snow didn’t argue that science was somehow more important, but rather that it was critical to understand both humanities and science. C. P. Snow described the divide between science and non-science in the harshest of terms – that it was “fatal” and “dangerous” for educated people to be so divided and specialised. This was fifty years ago, when the pressing human and scientific concerns of global climate change were not even on the table. A few years ago, I would have fallen into the trap of feeling that my literature degree was all that I needed to know. Two things changed: I married my husband, who is an engineer; and I began to teach grade seven, which required me to teach everything. One of the results of this was my writing of The Steel Lady, which combined Victorian culture with science and technology. Another was that my classroom benefitted not only from my knowledge, but from my husband’s, as I sought his support in teaching physics and electronics. Not everyone is so lucky. What my students made clear to me yesterday is the same thing Snow that made clear all those years ago – we cannot afford to do this anymore. We cannot afford to divide our education, and feel superior in our beliefs and in our logic. There are enough divides between us – our education shouldn’t be one of them. We need science, or we can’t hope to understand our universe; we need literature and the humanities, or we can’t hope to understand each other. As C. P. Snow put it, “Isn’t it time we began?” |

Author

Jane Perrella. Teacher, writer. Expert knitter. Enthusiast of medieval swordplay, tea, Shakespeare, and Batman. Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed