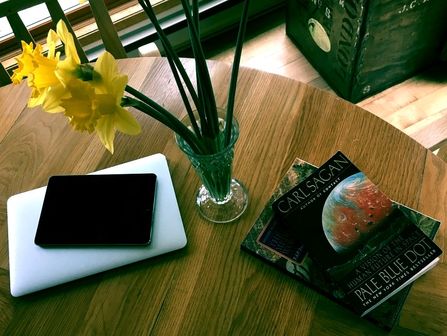

One debate in education is brought to my attention more frequently and more fiercely than most others: to what extent technology should dominate our classrooms. Most recently, I heard it between teachers at a workshop on iPads in the classroom. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the heavily voiced opinion was that technology – and iPads in particular – was king, and that non-technological methods – textbooks in particular – were categorically useless. Despite my dismay, I understand how we got here. Technology seems to divide teachers into two camps; there are those who feel that digital learning tools will make everything better, and those who have greater reservations, but who come under increasing pressure from the first group. That our students need to be educated about technology has become unavoidable, but being educated about technology also means acknowledging its limitations. It means acknowledging other ways of learning, including textbooks. A common reason for schools to avoid textbooks is the notion that the information in them becomes “out of date” and will need to be quickly replaced. Schools are shying away from buying textbooks for the same reason that many of us don't buy news media anymore: it's expensive, and we're under the illusion that we can get the same thing on the internet. This is a fair concern, but realistically, how does this compare to technology? Let's assume that textbooks need to be replaced every ten years in order to be accurate. Is it likely that a class set of iPads or laptops will make it that long in an elementary school, which the everyday wear-and-tear that they take? Experience suggests to me that they won't. Aside from cost, though, there is a difference in quality between paid and unpaid material. Though there are great sites and sources that will give away information for free, many websites simply do not do the same job as a textbook. Textbooks are expensive for a reason; they are, when done properly, carefully curated information presented for a particular audience – in this case, adolescent learners. They have been written by somebody who has had to put their name on the information. They are, as much as a single source can be, a reliable source. In some cases, these strange old fashioned tomes can yield an unexpected picture of the past. In my classroom, I keep a set of “Time Life Great Ages of Man” books. They were written in the 1960s and 70s, and they each detail a different period of world history. They aren't the friendliest looking books from the outside, but inside, they are fluidly written, and contain beautiful photo collections at the end of each chapter. One of my students was reading the book about the 1700s, and ask me why, in the introduction, the author commented on the fact that in his time, men were “trying to destroy the world.” I explained to her in broad terms the concept of the Cold War, which would have been relevant at the time the author was writing. Critics of textbooks would point to this as another example of how textbooks are archaic and useless; I see it as a chance to talk about authorial voice and bias, and the context in which history is written. These are issues and skills that are no less relevant to the modern digital user than they were generations ago; if anything, it is more important than ever that students have a base of information from which to make judgements. One critical skill in technology education is evaluating sources for their reliability, but in order to do that, you need to know things to begin with. Simply throwing students onto the internet to teach them “media literacy” is naïve, if that media isn't compared to something. Far from being inferior to digital media, textbooks and print media still provide a perspective that an internet search does not. They give us a glimpse into a moment in time and the author’s thoughts on it, and hopefully allow us to be inspired in our current moment by the writing of the past. As an example, Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot is arguably scientifically obsolete; it was published over twenty years ago, and it will not give you an up-to-the-minute account of space travel. What it will give you is inspiration and vision, and the perspective of someone who understood that knowledge is ever-changing, so long as we pursue it. Sagan’s book is full of hope, that instead of turning down a path of ignorance, we will look together to planets of our Solar System, and find a way to reach them. That our knowledge has progressed beyond what Sagan knew does not make him wrong; hopefully, it makes him right.

0 Comments

|

Author

Jane Perrella. Teacher, writer. Expert knitter. Enthusiast of medieval swordplay, tea, Shakespeare, and Batman. Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed