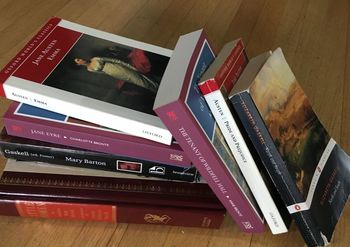

This is not a pile of women's fiction. It is a pile of books. This is not a pile of women's fiction. It is a pile of books. I have been querying agents and publishers about my novel, The Steel Lady, and I have come across a category that makes me scratch my head – women’s fiction. It is usually given within a long list of other genres – young adult, science fiction, mystery, fantasy – that the person in question will consider. It made me think of when I was about sixteen, and I was visiting my grandma. My dad came in to borrow a book – a novel by Georgette Heyer, who wrote romances set in the Regency. When he left, my grandma made a derisive sound, and when I asked what the problem was she said, succinctly, “I don’t understand it. Those are women’s books.” It’s one thing for someone raised three generations ago to hold that opinion, but it seems problematic that the category remains intact within the publishing industry. The aggravating thing about it is that whenever I see an agent or publisher who accepts women’s fiction, I’m caught between delight and annoyance. I’m fairly certain that my novel falls well within the parameters of women’s fiction, as it has a female protagonist, and focuses on her development, growth, and relationships. It is a troubling assumption to stamp this kind of fiction as purely of interest to women. Let’s look at two examples of fiction that have stood the test of time: David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens, and Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Bronte. Jane Eyre is easy to label as women’s fiction. It charts the development of the young woman in its title, and a sizable amount of the novel focuses on the love story between Jane and Mr. Rochester. So then, is David Copperfield… men’s fiction? It focuses on the growth and development of a male protagonist, but no one would think to categorize David Copperfield as anything as pejorative as “men’s fiction,” even if such a term existed. I am no less guilty of this than anyone else. When I have assigned the Classics Project to my students, and they ask which book they should read from my list of suggestions, I have in the past recommended Lord of the Rings, Dune, and Dracula to the boys, and Jane Eyre, North and South, and Pride and Prejudice to the girls. This is ridiculous and needs to stop. All the books on the list are ones that I have read and loved, because they are wonderful, engaging books. The gender of the protagonist was irrelevant to me, and is equally irrelevant to my students. Then there are the novels that would seem to be women’s fiction, that aren’t. In my own novel, the story is not simply that of one young woman’s life, but also the story of enormous technological upheaval and change. As soon as it includes speculative elements, does it cease to be women’s fiction? This seems odd, particularly since genre fiction is so often where the strongest female characters are to be found. For example, does The Hunger Games count as women's fiction? It has a female protagonist. What about Marissa Meyer’s Lunar Chronicles? They, like Jane Eyre, are even named after their female characters. How about James S.A. Corey’s Caliban’s War? Two of its character narrators are Chrisjen Avasarala and Bobbie Draper, pretty much two of the toughest women in fiction. Why are these not pigeonholed as “women’s fiction”? A term like women’s fiction excludes in both directions. It excludes in what it leaves out – science fiction, dystopian fiction, fantasy, mystery – and in who it leaves out – namely, men. If women should read David Copperfield (and they should, by the way), then men should also read Jane Eyre. There is a wonderful and wide selection of fiction that includes female voices, but it is not enough for these voices to only be heard by women. It is imperative that women read stories of men, and that men read stories of women, and that we all read stories because move us and entertain us. Our stories are how we create empathy, and it does us little good to only empathize with our own side.

1 Comment

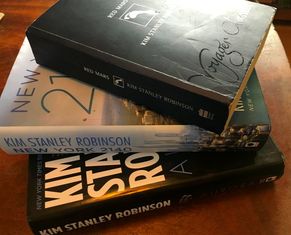

When Three Square Market, a Wisconsin vending machine company, announced this week that it would offer microchip implants to its employees, the reactions ranged, understandably, from delight to panic. Some hailed the next wonderful step of the computer age, while others predicted the coming onslaught of our robot overlords. There is legitimate enthusiasm over the increasingly science-fiction-like places that technology might take us, and legitimate concern over the ugly path it might lead us down. It seems to me that a question that is less addressed is not what technology we develop, but who develops it for us. Kim Stanley Robinson, the author of Aurora and New York 2140, recently commented that “we live in a present mixed with various futures overshadowing us. In essence, we live in a science fiction novel we all write together.” It’s an almost optimistic idea, but nowhere does Robinson suggest that we all have an equal hand in the writing. Rather, our world looks to be on the path of Robinson’s Mars trilogy, where large corporations have a major say in the exploration and exploitation of the Red Planet, sometimes to the detriment of the inhabitants of both Earth and Mars. In writing the future, we can often forget to ask who does the writing. Three Square Market is not the only example. The man who seems most poised to be Robinson’s fiction made real is Elon Musk. We stand in awe as he advocates for exploration and colonization of Mars, for the preservation of this planet through alternate energy, and more recently, for the development of brain implants to treat serious diseases. Much as I admire Musk’s goals, it is worth remembering that he is not a saviour. He is the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, and however noble his intentions, his position as head of two corporations comes with strings. We cannot, as citizens, simply accept that human development and innovation comes solely from corporations designed not for our benefit, but for our consumption. In every field – from nanotechnology to space exploration – there is a profit motive, and so there must also be an active participation from governments to ensure that it is not merely the interests of corporations that are served. To his credit, Musk seems to know this. He actively seeks the investment of governments in his proposed plans for Mars, because governments are the only one who can assemble the kind of capital that such a plan requires. They can assemble it because they serve a large group of citizens, who ultimately get some say in their expenditures. Government participation and regulation does not come from a vacuum. It requires citizens who are sufficiently aware of the implications of developing technology to demand that their governments have a say over how those technologies get used. It demands, frankly, more work from all of us, both to learn the technical underpinnings that we are permitting, and to debate how far we will permit them. It demands that we bother to participate in government process, because we will not be permitted to have our voices heard in a corporate boardroom. Some will say that this is a fight that we have already lost. That corporations will advance their goals and technologies unchecked by the needs of humanity. I contend that we have not yet encountered that fight, possibly because we are still too delighted by the spectacle that such innovation gives us. We are no different from the Victorians wandering through the Great Exhibition of 1851, marveling at the heavy industry that was to improve every echelon of life, without calculating its cost. We have no excuse to be so naïve. Writing science fiction, true, good science fiction, requires on some level knowing science fact. If we are to be the writers of the science fiction novel in which we live, we first need to understand the world from which we write. Given that we have access to the largest and most accessible repository of knowledge that the world has ever known, we have a good place to start. |

Author

Jane Perrella. Teacher, writer. Expert knitter. Enthusiast of medieval swordplay, tea, Shakespeare, and Batman. Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed