|

When I woke up this morning, I did not expect my knitting pattern website to be embroiled in politics. Yet that is what has happened, as Ravelry, the “Facebook of knitting” as the Washington Post commented, has banned Trump supporting post. Yes, a knitting website feels that it needs to take a political stance against the current President of the United States, and is getting backlash for it. This is the world in which we live.

I’m honestly not sure how I feel about this. Trump scares and worries me as much as anyone, and I keep thinking that he can’t appal me more, until he does. And yet some have pointed out that to ban a certain viewpoint in the name of inclusivity is fundamentally flawed. They have a point. The problem is, both support for and opposition of Trump are now as much emotional stances as reasoned ones, and any discussion about it almost inevitably descends into complete incivility. This, again, is the world in which we live. What interests me most about this story is how befuddled people were that a knitting (and crochet) website gave a political response of any kind, much less such a stark one. It speaks to the stereotype of what a knitter is – reclusive and grandmotherly, and certainly not political. Given its associations, knitting would seem to be the ultimate act of conformity and complacency. It really isn’t. Knitting is subversive in its very nature, because it doesn’t have a structure or limit that to which you must adhere. I’ve often thought that knitting had a lot in common with computer coding, right down to the fact that it is binary (with knit and purl stitches) and the fact that the “pixilation” of the work allows it to be, like an image on a computer screen, anything you want. In an era where mass market production is the norm and we produce so little with our own hands, knitting is a protest, a therapy, and a creative endeavour. (Really, you should try it.) Should Ravelry have made this decision? They had to, really. In this world and in these debates, there is no sideline, and those who do not wish for their tolerance to be bulldozed need to express that paradoxical “intolerance for intolerance.” The site administators suumed this up by stating that “formal political neutrality is not tenable” in such an environment. As a social and interactive platform, Ravelry was required to pick a side – and given what they do, their side doesn’t surprise me.

1 Comment

It is difficult for me to write about the current changes to the Ontario Health curriculum with anything other than fury. Even as far removed as I am from it, as a teacher in British Columbia, my reaction to a reversion to a 1998 health curriculum is visceral; as an elementary teacher who teaches health, it fills me with rage. But rage is, pretty evidently, not a helpful direction in this particular situation, as there is already plenty of it.

The absurdness of throwing out a health curriculum that had been updated and implemented for three years should be obvious, but as it isn't, let's think about the context in which its predecessor, the 1998 Health curriculum, was created. The date is particularly weird to me, as someone who currently teaches grade seven; in 1998, I was in grade seven. This twenty years of separation should be horrifying on its own. In 1998, there was no social media. The internet was only just something that educators were beginning to grapple with. The legalization of same-sex marriage was seven years off. And nowhere in our sex education classes (what little of it there was) was there ever a mention of gender identity. To teach such a curriculum now would ignore vital elements of a student's sexual and social development. Teachers are not the same as curriculums. While it is frustrating that the 1998 curriculum has held on as long as it has, teachers in Ontario are perfectly capable of supplementing it with current concerns and relevant social issues. Except that now, they aren't, following Doug Ford's announcement of punitive action for those who dare to teach anything other than the inadequate 1998 curriculum. This includes topics such as consent, gender identity, and cyber safety relating to sexuality for students below grade 9. There are two problems with this logic. One is the content itself, and the other is the contention of the age to which it should be delivered. Let's consider the content first. The opposition to the new curriculum seems to be based on the belief that schools will be indoctrinating students with beliefs that are contrary to those of the parents, regarding consent and gender identity. The counter to this is simple; these lessons are not beliefs, they are facts. When discussing these issues within my own health class, I do not tell my students what to believe. We discuss what is legal in Canada and the rights that are protected by Canadian law. These are not debatable, and consultation with parents should not remove these anymore than they should remove facts from the Social Studies or Science curriculum. Canada has laws protecting the rights of people of different sexual orientations and genders. Canada has laws around sexual consent. Parents are at liberty to disagree with these laws (because we have laws that protect belief, as well) but removing this information from their children's education could lead to serious harm later in life. The other often-cited objection is that the matters of gender-identity and consent are not "age-appropriate," a phrase that mirrors the 1998 curriculum's expectation that "students will describe age-appropriate matters related to sexuality." Again, the counter to this is straightforward: "age-appropriate" in 2018 is not the same as "age-appropriate" in 1998. I wish it were otherwise, but it isn't, and pretending that children in elementary school are not exposed to a vast array of sexual content is wishful thinking. They are, and if their only education in sexual health is via the internet or their friends, it will set them up for a deeply confusing, frustrating, and potentially dangerous adulthood. All of this is without even addressing the vastly positive results that I have witnessed in teaching an extended, comprehensive sexual health class. I have seen students come alive at the mere possibility that the feelings they have for the same-sex are considered okay. I have been privileged to watch students able to discuss their mental health anxieties in front of their peers, and realize, to their relief, that they are not alone. And I have seen male and female students express empathy and concern for the differing experiences of the opposite sex as they move through puberty. These students are 11, 12, and 13 years old, and these issues desperately matter to them. What is age-appropriate for our students today, and for the students of Ontario, has to reflect their experiences and their context, which are radically different from mine, twenty years ago, in 1998. In their empathy and their curiosity about themselves and each other, these changes are often for the better.  My La Patrie Etude. "Still purrs, like it was yesterday." My La Patrie Etude. "Still purrs, like it was yesterday." I have told many people these past few months that I am not a music teacher. This, despite the privilege of having thirty guitars in my classroom, and despite the fact that I sometimes teach music to two classes besides my own. I stand by what I said. Music was never forced on me. When I was seven, I told my parents I wanted to play the violin. I did. I played it for two years, under the kind of strict instruction that seems to go with learning the violin. When I was nine, I told my parents I would not play violin anymore. They didn’t stop me; music was a choice. My violin teacher, on the other hand, told me I was a quitter. Now that I think about it, she only confirmed the decision that I made. My next instrument didn’t come with an instructor, at least not at first. My next instrument was a guitar – a cedar-top classical La Patrie. It sounded warm, and it still does. It was an obvious choice of instrument for someone who always wanted to sing.. On the afternoon in grade six that I got it, I went to my room and picked out a song on it. I didn’t know the names of the strings yet, but I could recognize the intervals of “Ode to Joy.” My first year or so of playing the guitar, I played it… badly, if I’m being honest. My learning was slow, until, on a camping trip in the Bowron Lakes, my parents’ friend John quietly asked if he could see my guitar. He didn’t say that he could play campfire songs like a demon, or that he knew all the lyrics to every song, or that he had a voice you could hear across the lake. He simply reached for it, and started to play. That is how I learned. Watching. Singing along while John led campfire songs. Gradually, as I got older, as we kept camping together, it became me leading the songs, or both of us. I had played with John for years when I learned that he couldn’t read music; he just read chords, and sang with joy, and everyone joined in. I have had a smattering of music training. I played clarinet for six years. Tenor saxophone for four. I even took piano lessons in university, proudly playing the scales I was never forced to play as a child. I have loved all of it, but for me none of it compares to guitar and a song. None of it has the force of inspiration that guitar has, the instant desire to play until your fingers are callused, that a guitar has. You can learn a song in an afternoon, or you can spend a lifetime learning everything that it can do. Preferably, both. Music always takes time and patience, but the last thing that I have ever wanted to impart for music is exasperation. I’m not always successful at this. Sometimes my insistence that we learn harmony, or the insistence on learning chords on the guitar, frustrates my students. I know it. I see it. But I also know that a guitar has a singular power to be both a comfort in solace and an invitation to be social. I can’t think of another instrument that fills that role. There was a hashtag on Twitter yesterday that ran #WhatMusicMeansToMeIn3Words. Impossible. How to tell what a lifetime of music means in three words? The best that I could come up with was “Passing a torch.” Guitar was passed to me. The ability to make joyful noise was passed to me. I wasn’t so much taught as I was inspired. I try to do the same. I am not a music teacher. I simply offer someone the makings of a fire, and set it alight. “He doesn’t… exactly know, no,” Josephine admitted. Writing is scary. I say this, in spite of being someone who writes. I say this, in spite of being someone who assigns creative writing to her students. In fact, I say it because of those things. I am no less scared of writing than anyone else. And if I'm honest, I'm sort of terrified to let people read my writing. It's like removing parts of my own brain for people to look at. I have no formula of how to make that easier, other than to just do it. A few months ago, a student walked into my class after a swim practice, and I joked that I would write a story about mermaid students. So I did. This is that story. (Teen. Some swearing.) Till Human Voices Wake Us

Jane Perrella Josephine dodged the incoming ball, but only just. It whizzed past her head and skittered over the surface of the water. There was no time to be graceful; she threw herself backwards, gulping down a mouthful of water as she did. She came spluttering up out of the water, and glared across the pool at Crispin. Her teammate flashed her a wicked grin. “You could have caught that,” he said, shaking droplets out of his dark hair. “With what?” Josephine yelled over the echoes of the pool. “My mouth?” Crispin gave another lopsided grin, and dove under the water. His tail flashed above the surface as he did. Josephine would never tell him so, but she was a little jealous of his tail; it was iridescent blue, flashing turquoise when it was above water. It matched the scales on his forearms, and the webbing between his fingers. It was flashy, loud – like Crispin himself. Hers was nothing like as pretty; it was indigo, such a dark purple that underwater it looked almost black. Josephine sighed, and flicked her gaze to the clock above the pool. If she was going to be on time for her first block, she needed to get out now. Her coach’s whistled seconded her thought, and she swam for the cubicles at the edge of the pool. “Wait up, Jo!” Josephine glanced over her shoulder in time to see Crispin gaining on her, angling, as usual, to snatch away her cubby from her. She kicked harder, but she was no match for Crispin; his tail was broader, and three of his fingers were webbed, the way a merman’s always were. He always would be faster than her. He swam into the cubby and yanked the curtain closed. “Crispin! What the hell?” she yelled. “It takes me twice as long as get ready as you!” “And who’s fault is that?” he called back over the wall. “Yours!” she snapped. “My clothes are in your cubby, you moron!” “Keep your scales on,” he muttered. “I’ll pass them over the wall.” Josephine slid into the cubby beside him. The bottom of the cubby was an alcove of the pool itself. Josephine gripped the handles that hung over the water, and pulled herself up onto the ledge around the outside of it. She glanced up, looking for her clothes, as she waited for her scales to become skin. She grimaced at the awkward stage between having a fin and having actual legs that made clothes impossible. “Crispin? If you don’t give me my clothes, I swear, I am-” “Will you relax?” came Crispin’s impatient voice. “It’s not like I can stand on my freaking fin.” “How the hell do you still have a fin?” Josephine demanded, looking down at her own ankles. They were still slightly scaled, but they were, well, ankles. “How the hell do you change so fast?” Crispin retorted. “And follow up question – if you can change the entire structure of your lower body that quickly, then why are you always late for first block?” “Clothes. Now. And if you drop them in the water, I will personally skin you, you freak,” Josephine added. “Freak? Really? You’ll be calling me Fishguts soon, like the rest of them.” Josephine winced at the bite of anger that came into Crispin’s voice, and got unsteadily to her feet. Her clothes came over the top of the cubby – very nearly falling into the water. She towelled off and changed quickly into a t-shirt and jeans, her legs strengthening as she did. She pulled her dark hair into a messy knot low on her neck, and pushed open the door of the cubby. Crispin, somehow, was already out, wearing his standard black t-shirt and jeans, though at least these ones didn’t seem to have holes in them. He threw her backpack to her, and as she caught it, she noticed a flash of turquoise scales on his forearm. “You aren’t dry,” she said. Crispin glanced at his arm. “Shit,” he muttered. He shrugged. “Doesn’t matter.” “Of course it matters,” Josephine said. It was easier to hide being a mermaid than merman. Her only scales were her tail. “Just dry it off.” “Jo, seriously, it doesn’t matter,” Crispin said roughly, running a hand through his hair and looking away. His hand came out of his wet hair with a dusting of turquoise scales on it. “You don’t have to be careless about it,” Josephine said. Crispin turned to walk away, and Josephine trotted to keep up with him. “I’m not,” Crispin said shortly. Josephine bit her lip. “Hey, come on, the lubbers don’t need to know that-” “They already know,” Crispin snapped. He glanced sideways at her. “Well, about me, anyway. And I don’t give a shit what they think.” Josephine glanced at him, and decided to drop it. She knew he was lying, but this didn’t seem the time to mention it. His scales were fading, anyway. Soon they would both look almost normal. Josephine slid into a desk near the window as the bell sounded, and dumped her backpack at her feet next to her. Her first block teacher, Mr. Tingey, began passing out sheets of an enormous poem. Josephine glanced down at the paper, and blinked. The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock, by T. S. Eliot. An odd choice. Old. “Hey Mr. T?” Mr. Tingey sighed and glared at the back of the class. “Do you know how to raise your hand, Mr. Lausanne?” Josephine glanced over her shoulder, to see Crispin giving his sarcastic grin. “Flaw in my genetics, Mr. T. I was wondering, isn’t some of this poem racist?” Mr. Tingey raised an eyebrow in Crispin’s direction. “I assume you mean specie-ist, Mr. Lausanne.” Crispin shrugged, and slouched lower in his desk. “Whatever.” “Conveniently, Mr. Lausanne,” Mr. Tingey said dryly, raising an eyebrow, “that is one side of our discussion.” Josephine tried to ignore the groans that followed, and listened to the lilting of Mr. Tingey’s voice as he read. He always read the poems. He said it was because they understood it better. Josephine was pretty convinced that he read them because he liked to hear the sound of them. The rambling back and forth of Eliot’s poem folded over her, until the very end. I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each. I do not think that they will sing to me. I have seen them riding seaward on the waves Combing the white hair of the waves blown back When the wind blows the water white and black. We have lingered in the chambers of the sea By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown Till human voices wake us, and we drown. Josephine frowned. She could see why Crispin had asked – though she didn’t know how he had known. The poem wasn’t exactly anti-merfolk, just… eerie. Worrying. “Well, Mr. Lausanne?” Mr. Tingey said. Crispin shrugged. “Seems specie-ist to me.” “Bullshit,” muttered Flynn Roy. He was sitting two seats away from Crispin. If he hadn’t been, Josephine was pretty sure Crispin would have kicked him. “You had an opinion to add, Mr. Roy? An articulate one, preferably?” Mr. Tingey said, sharpness underlying his voice. “There’s nothing specie-ist about this,” Flynn said, throwing a hand carelessly in the air. “You think the mention of mermaids means nothing?” Mr. Tingey said. “It means he wrote about mermaids. Isn’t that good?” Flynn said. “Doesn’t that mean he thought they were worth writing about?” “He wrote about them as singing sea-girls that drown sailors,” Crispin snapped. “So?” shrugged Flynn. He grinned maliciously, and elbowed his friend. “Aren’t they?” Josephine was vaguely aware that Crispin was exploding, but she didn’t hear his response. She wasn’t looking at Flynn anymore – she was looking at his friend, who had lifted his head when Flynn elbowed him. Tristan Raydon. Perfection. Tall, handsome, blond hair falling into his blue eyes. The star striker of Riparian High’s Soccer Team, and the dream of every girl there, human or otherwise. And, as ever, completely unaware that she existed. Josephine directed her gaze back to the poem as heat rose in her cheeks. Sea-girls. Singing mermaids. Honestly. She might as well be a rhinoceros for all the good that it did her. “Miss Marella?” Josephine’s head snapped up. Mr. Tingey was looking at her expectantly. “Sir?” “Your thoughts, Miss Marella, now that Mr. Lausanne and Mr. Roy are done tearing each other apart,” Mr. Tingey said, raising an eyebrow. Josephine swallowed. A ream of expletives scrolled across her brain, as she searched for what to say. “This poem…” she said slowly. “It’s old.” “Yes, Miss Marella,” Mr. Tingey said wearily, “and I’m practically a dinosaur. Your point?” Josephine glanced at date, and frowned. “There were no mermaids then.” Mr. Tingey’s head tilted to one side, his eyes glittering. Josephine could hear the shuffling of students around her, as they decided whether or not to listen. “Go on,” Mr. Tingey said. Josephine frowned, and licked her lips. “The mermaids in this poem… they aren’t real mermaids, they’re myths. How could he be specie-ist if he was writing about something that wasn’t real until we made it so? It seems… unfair to judge him from … our perspective.” Josephine swallowed. “And anyway, the mermaids are metaphorical.” “For?” Mr. Tingey said. “For what he can’t have,” Josephine said. She made a point of not looking at Tristan. “He says he doesn’t think they will sing to him. It doesn’t matter whether they are mermaids, because they are fantasy.” The class had gone quiet, and Josephine felt her cheeks growing hot. Flynn was wearing a lopsided grin, and Crispin was glaring thunderclouds at her. Tristan was doodling on his notebook. “Thank you, Miss Marella,” Mr. Tingey said softly. A smile pulled at one side of his mouth. The class wound on, outside of Josephine’s awareness. She read through the poem again, making notes in the margins. She tried not to hear Flynn and his friends making fun of Crispin. She didn’t look at Tristan. When the bell rang she scooped up her books and hung her head as she made for the door. She was vaguely aware that Crispin was behind her, in that way that she always knew where he was. She headed out into the hall. “Hey Fishguts!” Josephine froze, and found herself glancing down at her sandaled feet. Had she spilt water on her feet? Did she have scales? Could everyone… no, of course. They were talking to Crispin. Josephine relaxed slightly, and felt guilty for doing it. Josephine turned, to see Flynn and a group of his friends walking towards Crispin. It included Tristan, she noticed with a thump of her heart. “What, Roy?” Crispin muttered. “Sensitive as always, Lausanne,” Flynn sneered, taking a drink from a water bottle in his hand. “Always fun to see you be a whiner in Lit class.” “Go to hell, shithead,” Crispin growled back. He glanced around warily. Josephine could see the other students in the hall slowing to watch the spectacle. Flynn grinned. He took a quick step to Crispin, and dumped his water bottle over Crispin’s arm. Josephine froze. Crispin swore and jumped away, but it was too late. Turquoise scales bubbled across his skin, and webbing bound together the fingers on his right hand. Gasps and laughter skittered across the hall, and Crispin’s face flushed red. In the ensuring silence rang the harshness of Flynn’s laughter, and that of his friends. Josephine looked at Tristan. He wasn’t laughing, but… he was smiling. Josephine couldn’t tell why, and it made snakes coil in her stomach. “Seriously, Lausanne, that is some weird shit,” Flynn said between his laughter. Quiet settled over the hall. Josephine swallowed, and looked at Crispin’s face. He was staring at his hand. “Let’s go, Crispin,” she said quietly. “At least one human girl can stand to look at you,” Flynn said. Josephine swallowed, hoping her face gave nothing away. “Crispin,” she said. She touched his arm, and he jumped and snatched it away. He looked up at her, his dark eyes tangled with emotion, and nodded slowly. They both turned away from Flynn. “Seriously, Lausanne, was your dad a trout?” Flynn called after him. “Crispin, don’t-” Josephine began. It was too late. “At least I know who my dad is, you prick,” Crispin called over his shoulder. Flynn was after Crispin so fast that he elbowed Josephine out of the way, and for a moment she didn’t know what was happening. She staggered, and someone caught her. She could see Flynn with his hands gripped on Crispin’s shirt, Crispin with his eyes crackling fire at Flynn. And slowly, she came to realize who had caught her, and who was murmuring the words, “are you all right?” against her ear. Tristan. Between everything that was going on, it was a small miracle she didn’t throw up on her shoes. Mr. Tingey’s door banged open, and the tall teacher stood in the hall, glaring at the two boys. “Roy,” he said, in a calm, even voice. “Put him down. And leave.” Flynn’s hand uncoiled from Crispin’s shirt. He muttered, “See you after school,” and backed away. “The rest of you,” called Mr. Tingey. “You have something else to do.” Slowly, the watching students dispersed. Josephine turned her head, trying to calm her pounding heart. Tristan Raydon was slowly letting go of her elbow, still asking, “are you okay?” Which meant… that Tristan Raydon had been holding her elbow. This seemed strangely important. Josephine nodded. “I, yeah, thanks.” Tristan frowned, his eyebrows crinkling over his sky-blue eyes. “It’s Josephine, right?” He knows my name. “I… yeah. I’m Jo.” “Sorry about that, Jo,” Tristan said, smiling a little. “Flynn can be a bit… he doesn’t mean anything by it.” Josephine could feel herself melting. It was the same feeling she got when her legs became a fin – a feeling at once sinking and blissful. “I,… yeah, I know. Thanks,” she smiled weakly at him. “I… I’ll see ya,” Tristan said, as he walked away. “Yeah,” Josephine said. “I,… see ya.” She stared after him for a while, until she blinked, and turned to see where Crispin had gone. She saw him and Mr. Tingey heading for Mr. Tingey’s classroom door. Reluctantly, she followed. “You’re going to get yourself into a lot of trouble one of these days, Mr. Lausanne,” Mr. Tingey said, as Josephine walked in. “I can handled Flynn,” Crispin said. “There are more adversaries in the world than just Flynn Roy,” Mr. Tingey said softly. He turned to face her. “Miss Marella, do you have a bottle of water?” Josephine blinked. “I… yes?” “Can I borrow it please?” he said gently. Josephine rummaged it out of her bag, and passed it to Mr. Tingey. She glanced sideways at Crispin, who shrugged. Mr. Tingey unscrewed the cap from the bottle, and poured it over his forearm. Josephine gave a started squeak, while Crispin muttered “what the hell?” Both of them stared. Mr. Tingey’s arm had gone a shimmering shade of silver-white, with fine scales. The webbing of his pinky and ring finger made his hand seem longer, as he held it up to his eyes to examine it. Josephine gasped; along the scales on the bottom of his arm was a nasty black scar – one she had never noticed before. Mr. Tingey looked at her. “As I said… there are more adversaries in this world than just Flynn. Though luckily for you, Mr. Lausanne, there are also more allies than just Miss Marella. Now. You both have an art class, do you not?” Josephine stared into the mirror on the door of her locker, and sighed. It didn’t seem to matter what she did to her mess of dark hair, it was still just that - a mess. She had once considered the possibility of giving up morning swim practice and water polo, not only for her hair, but for the sake of hiding her secret. The idea was painful. Josephine closed her locker door, and jumped. Leaning against the locker beside her, a lazy grin on his face, was Flynn Roy. “Sup, Jo-jo,” he said, crossing his arms. “Can I help you?” Josephine said, genuinely puzzled and a touch annoyed. She wondered what faces she had been making into her mirror. Flynn’s grin widened. “Me? Nope. I’m here for my dumbass friend,” he said, nodding his head over his shoulder. Josephine glanced past him, and her stomach dropped away. Down the hall, leaning against a locker like he wasn’t listening, was Tristan. He glanced up, and saw her looking down the hall at him. He flushed to his ears, and stared at his shoes. “He claims that you and Fishguts have a thing,” Flynn went on. “I say no dice. Which is it?” “I… what?” Josephine said, trying to comprehend his words, as well as their implication. “You and Fishguts.” Flynn rolled his eyes. “Fine, Crispin, whatever. Thing or not?” “No!” Josephine said, more forcefully than she meant to. She could feel her cheeks going red. “I mean, he’s my friend, of course, but he-” “Told you, dipshit!” Flynn yelled down the hall. Tristan cast him a horrified look, shifted his backpack, and turned and walked away. “Sorry Jo-jo,” Flynn said, turning back to her with a grin, “gotta-” “Go,” another voice said. Josephine turned to see Crispin walking up to them. “You have to go, you were saying,” Crispin said coolly. For a moment Flynn and Crispin glared at each other, neither of them speaking. Finally, Flynn flashed a grin. “Later, Fishguts.” “What did he want?” Crispin muttered, glaring at Flynn as he walked away. Josephine couldn’t help it – a grin spread across her face. “Crispin,” she said, her voice breathless, “I think, I think Tristan Raydon might… kinda like me!” She knew her voice was a squeal. She didn’t care. Crispin’s face was unreadable. The gaze of his dark eyes was flat and unfocused – if anything, he looked bored. “Hooray?” he said, raising an eyebrow. “Who cares? What was Flynn here for?” “Tristan, he wanted to know if you and I, were, you know…” Josephine trailed off, her face flushing as she realized how it sounded. Crispin stared for a moment, before he nodded. “I get it. Flynn checking you out on behalf of his lapdog?” “Tristan is not his lapdog!” Josephine gasped. “What the hell is that supposed to mean?” “Nothing,” Crispin said. Boredom in his voice again. Apathy, even. “I’m delighted for you. Send me a wedding invitation. Come on, we’ve got English.” “I don’t get this assignment.” Flynn complained as the class ended. “That’s cause you’re an idiot,” Crispin said as he shouldered his backpack. “Screw you, Fishguts,” Flynn snapped back. “Ever the poet, Roy,” Crispin said with a grin. “Crispin,” hissed Josephine, as she grabbed Crispin’s arm and hauled him out of the class. “Don’t antagonize him.” “Why not?” Crispin said. “Worried he won’t report to your lover boy anymore?” Josephine rolled her eyes. “I should never have told you.” “Nope,” Crispin said cheerfully. “You will now have to endure my merciless mockery.” “I could always drown you,” Josephine replied. “No, you couldn’t,” Crispin said with derision. “I can breathe underwater.” “We still writing the last verse of that song today?” Josephine asked as she headed for her locker. Crispin was a magician with a guitar – Josephine wasn’t sure if it was because he was merman, but his long fingers could fly across a fretboard like no one else’s. They had been working on a few songs together; she wrote the words, and Crispin wrote the music and played the guitar. He had asked her to sing a few times, but she didn’t like to. Crispin glanced up, and his face locked down into an expressionless mask. “I may be, but it doesn’t look like you are.” Josephine looked up to where Crispin was looking. Her heart leaped into her throat. Tristan was standing in front of her locker, looking alternately at her and at his feet. She turned to tell Crispin that she would need a moment. He was already gone. She walked slowly towards her locker, and gave Tristan a small smile. “Uh, hey,” she said softly. “Hey. Yeah, hey,” Tristan muttered, looking up and then back at his feet. Josephine resisted the urge to giggle. It seemed impossible that this superstar could be nervous, but here he was, completely tongue tied and unable to talk. Talk to her. Just her. “So, Jo… I mean, Josephine, I was thinking, wondering, um…” Tristan looked up, and seemed to steel himself against his question. “So, would you help me with Tingey’s poetry project?” Josephine’s heart sank, and it must have shown on her face. “But, also,” Tristan said quickly, “maybe… we could get a coffee, or something?” Josephine looked up and let a grin sneak onto her face. It was the worst possible way she could have been asked out, and it made her tingle down to her toes. “Yeah, sure. Love to, actually.” *** Josephine walked through the hall at the end of the following day. She shouldered past the other students, but she barely saw them; her mind was on the previous afternoon, on Tristan’s shy blue eyes, on the way he looked up from under his mop of blond hair, on his smile. She had barely tasted her coffee, she was so focused on him, as they flipped through poetry books, trying to find something for Mr. Tingey’s assignment that struck him. In the end, he had gone with “O Captain! My Captain”; not her favorite, but he liked it, so she had helped him do the analysis for it. She pushed open the music room door, and listened for the familiar thrum of the lower strings of Crispin’s guitar, the notes he played when he was thinking, or composing a song. She stopped in the doorway, and placed her backpack on the floor. She could hear the guitar. She knew it was Crispin; she felt like she wasn’t so much hearing the notes as she was hearing the way his hands moved. It wasn’t the lower strings, the reassuring rumble of the low E; instead she could hear the plaintive notes of the middle strings, and the singing whine of the high notes. He was tucked away in one corner of the room, sitting on his amp. He was playing a solo. It was the kind he played when Flynn really got to him, when he had a fight with his dad, when he missed his mum with an ache that wouldn’t go away. Josephine knew the sound; it was the sound of his heart pouring through his fingers. She realized that for the first time in as long as she could remember, she didn’t know why. She walked in quietly. She knew better than to say his name; he would stop when he was done. She sat on the floor in front of his amp, hoping that he might notice her there. The notes of the guitar finished, and he looked up, looking groggy and confused. “Hey,” he said softly. “Hey yourself,” Josephine said, with a small smile. “You okay?” Crispin shrugged. “Sure.” He looked back at the fretboard of his guitar. “How was your date with lover boy?” Josephine tried to scowl at him, but somehow it became a grin. “It wasn’t a date. We just worked on some poetry.” “Uh-huh,” Crispin said, raising an eyebrow. “Which is why you have that idiot smile on your face.” Josephine grinned wider. “I’m seeing him again on Friday. Just, you know, for school stuff.” “Does he know?” Crispin said, looking straight at her. Josephine blinked. “What do you-” “Does he know, Jo?” Crispin asked forcefully. Josephine bit her lip. She wished she didn’t know what Crispin was saying, but she did – did Tristan know she was a mermaid. She was pretty sure that no one at school knew. They didn’t play on the water polo team, except for Crispin, and she hadn’t…. lied exactly, about being merfolk, it had just never come up. With Crispin, it had always been different. His dad was proudly, militantly merman, and always had been – Crispin didn’t have much choice but to follow him. “He doesn’t… exactly know, no,” Josephine admitted. Crispin snorted. “You may want to tell him,” he muttered, idly playing a riff on the guitar, and looking back at his fingers. “Does it matter?” Josephine said, and instantly wished she hadn’t. “Does it matter?” snapped Crispin. “Does it matter that you’re lying to him about the single most important thing about you? Yeah, I’d say it does.” “It’s not the single most… you know, I’ve liked Tristan for ages,” Josephine said hotly, not sure where she was going with this. “Yeah. You’d mentioned,” Crispin said dryly. “So why can’t you let me enjoy this?” Josephine said, finding herself on her feet. “He finally knows who I am.” “No, he doesn’t,” Crispin said in a tight voice, getting to his feet. His face was flushed and his guitar hung limply in his right hand. He stood close to her, and she could see anger flashing in his dark eyes. “That’s my point.” “And that point is?” Josephine said. “That until you tell him, it isn’t real,” Crispin hissed. He had taken a step towards her. He swallowed, but didn’t back away. Josephine looked down first. “I… think it would be better if we worked on the song another day.” Crispin didn’t speak for a moment. She found that with her eyes dropped she was looking at his chest, and watching his shallow breathing rise and fall under his t-shirt. “Yeah,” he said softly. “Sounds good.” Josephine walked to the door, and scooped up her backpack without looking back. It was only as she began walking home that she realized that she still didn’t know what was bothering him. It seemed too late to turn back. Josephine slid into her seat for her Friday English block, and drummed her nails on the desk. Tristan and Flynn hadn’t arrived yet. Neither had Crispin. Josephine bit her lip. Crispin had been weird all week, so much so that this morning he hadn’t been at water polo practice. It wasn’t like him to miss a practice, and she still didn’t know what was bothering him. She was trying not to notice it, but she couldn’t deny it bothered her. Flynn and Tristan pushed through the door, Flynn grinning, Tristan smiling a thin smile. Tristan looked up and saw her. His cheeks went red, and he slid into the seat next to hers. “Hey,” he murmured, his hair falling in his eyes. Josephine tried to quell her butterflies. “Hey,” she said, and smiled. “All ready?” “Yeah,” Tristan said. He smiled back. “Thanks.” “All right everyone….” Mr. Tingey began. Josephine glanced around the classroom. Where was Crispin? She vaguely heard Mr. Tingey ask for volunteers to present their poems. There were a few tepid volunteers, until Mr. Tingey started drawing names at random. Tristan offered a stuttering interpretation of “O Captain! My Captain!” while Flynn laughed his way through “Charge of the Light Brigade,” which seemed wildly inappropriate. Josephine was about to offer to present on Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 130” when Mr. Tingey pulled another name and glanced up. “Mr. Lausanne.” Startled, Josephine glanced to the back of the class. She hadn’t heard or seen Crispin come in. He slid back the hood of his sweatshirt and moved to the front of the class. His movements were strange and halting, and he looked pale. She frowned. He hadn’t told her he was sick – he usually did. He stood at the front of the class, a paper in his hands, and Josephine realized that his hands were shaking. He gripped the paper tighter, and looked out over the class. He cleared his throat. “This is ‘The Mermaid,’ by William Butler Yeats,” he said. His warm voice rolled the poem over the class. “A mermaid found a swimming lad, Picked him up for her own, Pressed her body to his body, Laughed; and plunging down Forgot in cruel happiness That even lovers drown.” Josephine felt like ice water had been dropped down her back. She stared at Crispin, who refused to look at her. Mr. Tingey coughed. “Thank you, Mr. Lausanne. And your analysis?” “Aside from the literal meaning of the poem,” Crispin murmured, “the poem is… a story of letting your own happiness override the happiness and health of others. The mermaid is so caught up with who she chooses for love, she can’t see how wrong they are for each other.” Josephine didn’t hear the rest. She knew Mr. Tingey asked him questions; she was vaguely aware that Crispin answered. All she could think was that she was going to strangle him. The bell rang; Mr. Tingey announced that the rest of the presentations would be next week. Crispin headed for the back of the room, scooped up his bag, and was out the door. Josephine was grabbing up her books, her face hot with fury, when a hand landed over hers. “Hey,” came Tristan’s soft voice, “are we still…?” Josephine looked up, and gulped. She barely had time to enjoy the spine-melting look he gave her. “Yeah, of course. Your place, right?” Tristan smiled and nodded, and released her hand. Josephine dashed for the door, hoping that she could find Crispin. It wasn’t as though she didn’t know where he was going. She banged the door of the music room open, and was only vaguely aware of the shocked looks of other students as she stalked across the room to where Crispin was opening his guitar case. “Just what the hell was that?” she hissed. The music room was emptying, but still, she didn’t need everyone else to hear. “I would have thought that would be obvious,” Crispin muttered. He didn’t turn around. “Crispin!” she said. Exasperated, she stepped forward and grabbed the arm of his shirt. He turned sharply around, and suddenly buckled over. He groaned and put one hand over his right side. When he lifted his eyes, Josephine took a step back. He was crouched over his guitar case. His eyes had circles under them, and were gleaming with emotions she couldn’t read. She had never seen him like this. It scared her. “What the hell… in English, you…” Somehow, looking at him, she couldn’t bring herself to say it. He stood up, looking utterly miserable. “What about it?” “Was that a subtle hint?” she said sharply. “No,” Crispin snapped. “It was a non-subtle hint.” He turned back to his guitar. “Crispin, what-” “Leave me alone, Jo.” Josephine’s mouth opened and close again. She felt like he had slapped her. She stood staring at her friend’s taut shoulders, and wished she knew what to say. Instead, she did what he had asked, and walked away. Josephine curled her spaghetti around her fork, and curled her feet beneath her. She looked up at Tristan, who sat on the other end of the couch and smiled. “Thanks for making me dinner,” she said. “It’s really good.” It wasn’t. Tristan smiled sheepishly. “It’s what I know how to make. It’s what I always make when Mum’s out of town.” “And your dad?” Josephine asked. “He’s still at work,” Tristan said shortly. There was no offer of further information. Josephine frowned. This seemed to be true of much of what Tristan said. She had been trying to find openings in the conversations, ways to know a deeper version of him, but every time she did, she found herself hitting a wall. If Crispin had been there, he would have told her that Tristan did not have a deeper version of himself. Right now she didn’t want to know what Crispin thought. “You don’t have siblings, do you?” Josephine asked, as she set down her bowl of spaghetti. She was embarrassed that she didn’t know. Tristan shook his head. “No.” He gave a rueful smile. “Well, there’s Flynn, I guess.” Josephine gave a brief laugh. “Flynn? He your brother?” Tristan grinned. “Basically. We’ve known each other since, I don’t know, grade three? And he’s always been, you know, there for me. He’d call himself my wingman, but that’s cause it’s Flynn.” He raised a sheepish gaze. “Though, I guess… with you, he’d kind of be right.” Josephine felt her heart thump into her ribs. She looked down at Tristan’s fidgeting hands on his lap. She looked up, and found him leaning towards her. She shuffled herself towards him on the couch. He reached out, suddenly, and put his hand in hers. She looked up and met his blue eyes, wide and terrified. It almost made her laugh, but she couldn’t. Not around the butterflies in her stomach. He kissed her. It felt like melting. His lips were gentle, shy and nervous like him. She wondered what kissing Crispin would be like. She smothered the thought, and squeezed Tristan’s hand. *** Josephine eased herself into the pool on Monday morning, and felt the tingling sensation as her legs bound themselves into a tail. She let a grin spread over her face as she sank under the water, and swam out of her cubby into the pool. The warbling of the water filled her ears, and she rolled through the pool, dodging the other members of her team as they warmed up before practice. Josephine saw a flash of turquoise scales in the water, and turned to watch Crispin swimming through the water. Grinning, she took off after him, and grabbed his tail. Crispin jerked around under water and rose to the surface. As he did, Josephine found herself staring at the lean muscles of his chest. No, not his chest: at the purple bruises that circled the right side of his ribcage. Josephine rose above the water, and stared at him. “What?” Crispin said gruffly. “Your ribs,” Josephine said softly, barely audible over the sounds of the pool. “Crispin, what-” With a shake of his head and a look of disgust, Crispin dove beneath the water. Josephine stared after him as the coach called them together. She watched him move all through practice. He was slower, his movements less graceful. She could see pain on his face when he was jostled by another player. She let him be, left him to go get changed, and waited outside for him, her backpack over her shoulder. He took longer than usual. When he came out, he didn’t meet her eyes. “Cris,” she began. “We’re going to be late for class, Jo,” he said, walking past her. She moved in front of him. “What happened to you?” she demanded. He looked up at her, his eyes flashing and dangerous. “Nothing.” She had known him for too long to be afraid to be close to him. She grabbed his left shoulder, and pressed a hand against his right ribcage. He howled in pain, and pushed her away. “What the hell, Jo?” he demanded, facing her, his face furious. “Your whole ribcage is bruised. Why?” she demanded. “Got hit during practice,” he snapped. “Bullshit,” she returned. “You were hurt before practice. Tell me now.” “No,” he said. “Have you told your dad?” she threw back. Crispin opened his mouth, and closed it. An admission that he hadn’t. “Should I tell him?” she said. “Jo, please,” Crispin said. He lifted his eyes to hers, no longer angry. Pleading. Begging not to be asked. “What. Happened,” she said. Her hands felt cold and shaking. Crispin stared at the ground. “Flynn and his crew of assholes caught up with me, okay?” Josephine stared at him. “What do you mean, caught up with you? Flynn beat you up?” Crispin rolled his eyes. “No, he gave me flowers. Of course he beat me up.” “For… I… why?” Josephine said. She could feel tears standing in her eyes. She swallowed them back. “How the hell should I know?” Crispin muttered. “For fun? Because I turn into Aquaman when I get caught in the rain? Anyway,” he said, looking up at her and swallowing hard, “what the hell do you care?” “How can you say that?” Josephine said. Seeing Crispin hurt terrified her; his belief that she wouldn’t care positively wounded her. Crispin stared at her for a moment, and swallowed hard before he spoke. “They beat the shit out of me on Thursday, Jo. You saw me on Friday, and you didn’t care, because you were running off to lover boy-” “That’s such crap, Cris,” Josephine said, still standing in his way. “I asked you what had happened.” “Because you were pissed at me, Jo,” Crispin said tightly. “Not because it mattered.” “Of course it matters, Crispin,” cried Josephine. “You’re my friend.” Crispin gave a short, breathless laugh, and looked down. When he looked up, his smile held no humour. “Yeah, of course. Forget it, okay? We’re going to be late.” He shouldered past her, but she grabbed his arm. “Crispin. You said they. Who is they?” Crispin stared ahead. “Let it go, Jo.” “Who was there, Crispin?” Crispin dropped his head, his damp, dark waves of hair falling over his eyes. “Flynn. Glenn. Kaleb.” He drew a slow breath. “And Tristan.” Josephine let go of his arm, and stepped back from him. He lifted his eyes to her, dark and miserable. “I told you to leave it alone, Jo,” he whispered. “You’re telling me that Tristan was one of the ones who beat you up?” she said in a hoarse whisper. Crispin shook his head. “Just that he was there.” “But then… who…” Crispin sighed. “Flynn did most of the punching, if that’s what you want to know. His idiot friends just watched.” Josephine felt her chest tighten. “Even Tristan?” Crispin didn’t answer. “Crispin?” she said, her voice becoming shrill. “Yeah,” he said softly. “Did he… tell Flynn to stop?” Josephine said, her voice strangled on her tightening throat. She already knew the answer. If it had been anyone else, maybe he would have. But it was Flynn. Crispin gave a wry smile. “No. Just stood there. Told them they’d better go once I…” Crispin trailed off and looked away. “Once you what?” Josephine said. “Once I started coughing blood,” Crispin said. He attempted to give her a lopsided grin, and failed. It only made him look more miserable. Josephine felt shock beginning to ebb into anger. Tristan had kissed her a day after he had watched her friend get pummeled. Rage sang in her blood, and she turned abruptly and began stalking towards school. “Jo?” Crispin called to her, as he hurried after her. “Jo, come on, it’s okay, I…” He drew alongside her, and glanced at her face. He fell abruptly silent. *** Riparian High shone in the early morning sun as Josephine walked up its broad front steps. Crispin trailed behind her, his head bowed. She reached the top of the stairs, and glanced around the shallow fountain that glittered in the golden sunlight. Tristan, Flynn and their friends were gathered near the main doors. She began to walk towards them, when Crispin grabbed her arm. “Jo, please, don’t,” he said. She shook his hand off. She didn’t bother to ask what he meant. She knew. Tristan saw her, and smiled. He glanced behind her and saw Crispin, and his smile corroded into a frown. “Hey, Jo,” he said. “Were you there?” Josephine said sharply. Tristan glanced between her and Crispin. Flynn was glaring malevolently at Crispin. “What do you mean?” “When your wingman beat up my friend,” Josephine snapped. “Were you there?” Tristan looked at the pavement for a moment. It was all the answer she needed. “Why didn’t you do something?” she gasped, tears biting at her eyes. “What was I going to do, Jo?” Tristan said, pleading, stepping towards her. Josephine took a step back. “Anything! Stopped Flynn, or told someone! Told me, for starters.” “Jo, it’s Flynn,” Tristan said miserably. Josephine looked at him in disgust. “That’s a pathetic excuse.” “I’m not about to betray my best friend for some merman,” Tristan said hotly. Josephine went rigid. “Some… what?” Tristan swallowed. “Jo, don’t think that… I’m not, specie-est or anything, I just-” Josephine was no longer listening. She turned sharply, and walked towards the fountain. She dropped her bag, and kicked off her flats. “Jo,” came Crispin’s sharp voice. “Don’t!” She ignored him. She hopped over the concrete edge, and sank both of her feet into the water. It didn’t quite reach her knees. She turned to face Flynn, Tristan, and Crispin, and the crowd that was gathering around. Crispin was looking at her with anguish on his face. Flynn was staring in open-mouthed shock. Tristan was looking at her legs, growing horror showing on his face. Josephine didn’t need to look down to know what they were seeing: she knew that below her denim skirt was her increasingly obvious purple tail, binding her legs together from her knees down. She knew because of the pain. She couldn’t stand on her tail; it was like trying to stand on the very point of her toes on land. It grew more painful the longer it lasted, and yet she stayed upright, her fists at her sides. Tears pinched her eyes. She wanted to say something. She wanted to stare at Tristan and remind him that it was her that he had kissed only a few days before. That if he wasn’t specie-ist, he would still want to. That if he thought Crispin’s beating was fine because of his species, then what did he think of her? She didn’t say any of it. She couldn’t, and she didn’t need to. The look on Tristan’s face was answer enough. She cried out as the pain became too great, and collapsed. “Jo!” she heard Crispin cry out. She would have collapsed to her knees if she still had them. Instead her lower body slumped into the fountain, and her back hit the cool water, soothing and painful all at once. Her hair splayed in the water behind her as the bright sunlight seared her eyes, blinding her for a moment. Arms reached into the water and pulled her out, hauling her over the concrete edge. She squinted down at the arms wrapped around her to see delicate, webbed fingers, and turquoise scales glittering in the sunlight. She looked up at Crispin’s face. There were tears in his eyes. “Jo,” he whispered. Josephine hiccupped, tears spilling down her cheeks. “Jo, why?” he murmured, his webbed fingers touching her cheek. “Why would you do that?” Josephine reached up one shaking hand and brushed a tear from Crispin’s cheek. He flinched when she touched him. “Hey,” she said, “at least it’s real now, right?” The bell rang for first block. The crowd of students hesitated, before heading for the door. They left them, a merman and a mermaid, crying in the sunshine. It didn’t take long. Word spread fast through the students, and it was only a few minutes before Mr. Tingey and the principal, Mr. Montgomery, were there. Josephine knew she was crying, that Crispin was holding her tight against his chest and not letting go. She knew that Mr. Tingey was telling him to let go, to help her inside. She knew that Crispin was refusing. Her legs were slowly unbinding, enough that she could finally stand, and have Crispin help her into the school office. She knew she sat there only long enough to regain her strength, before being sent home for dry clothes. She looked into the office as she left. Crispin was gazing after her. His forearms still held a hint of shining blue. His face looked pained, stricken with guilt, and … something else. As she returned, she saw Flynn and Tristan walk into the office. She could see Stephan Lausanne, Crispin’s dad, speaking to Mr. Montgomery. She wanted to stay and watch, but knew she shouldn’t. The day passed in a quiet blur. No one spoke to her, and she barely noticed the swirl of voices around her. She didn’t have English that day, but as the bell rang at the end of the day, she found herself in Mr. Tingey’s classroom, staring numbly at the empty room. “Quite the day, Miss Marella.” She looked up at him, and gave a wan smile. “Crispin?” she said simply. Mr. Tingey nodded. “Mr. Lausanne finished speaking with Mr. Montgomery a few hours ago. The music room, I think?” Josephine nodded, and turned to go. “You must love him very much.” Josephine stopped. Any other day, it would have been an instant shock. Today, it took an instant to sink in. “Uh, … who?” Josephine said. He couldn’t mean Tristan, surely? “Mr. Lausanne. Obviously,” Mr. Tingey said, raising an eyebrow. “He’s my friend,” Josephine said. Mr. Tingey laughed. “Miss Marella, being a teacher does not make me stupid. Through the churning rumour mill of this school I have managed to determine that your… demonstration was in reaction to the violence against Crispin.” “Sort of,” Josephine said. “Sort of or not, that is not the act of a friend,” Mr. Tingey said. “Isn’t it?” Josephine said wearily. “No,” Mr. Tingey said sharply. “It is wholehearted sacrifice. I have yet to know that to come from anything but deep love.” “I’m pretty sure I don’t need this today,” Josephine muttered. “On the contrary, Miss Marella. I think it’s exactly what you need.” Josephine looked up to find Mr. Tingey looking at her, one eyebrow raised. “Um… how?” “Because it’s time you and Mr. Lausanne told each other the truth. He has always loved you, and you have always known where to find him.” Josephine pushed the door of the music room open. It was empty, except for the figure at the end. Crispin was standing with his back to the door. The strap of his electric guitar, black leather with embossed blue waves, stretched over his shoulder blades. He was playing a solo again, yet this one seemed… brighter, somehow. She walked into the room, but somehow, couldn’t quite make it all the way across. She stared at his back, at the waves of his hair that curled at his neck. She thought about how she always knew what he felt, and how she could never hide anything from him. She thought about his laughter and his music, and how it was better than even the sounds of the sea. The song changed to chords, and she could hear him singing softly. “I look for rhymes amongst the pebbles on the beach, Searching for what will always be just beyond my reach.” Her words. Their song. She coughed. Crispin turned, and lifted his eyes to her. “Jo,” he breathed. Josephine closed the distance between them. Crispin pulled the patch cord out of his guitar, and swung the guitar around to hold it against his back with one hand. He took a sharp step towards her, and wrapped one arm around her. His fingers splayed against her back, and he yanked her against him. Josephine caught her hands on his neck and the strap of his guitar, and lifted her mouth to meet his. If kissing Tristan had felt like melting, kissing Crispin felt like being lit on fire. It felt like so many missed opportunities finally made right, the slow passion of so many years of friendship crushed into one spinning moment. It felt dizzying and yet perfectly, completely right. Crispin pulled his mouth from hers and gasped. “So, um, can I put down my guitar, and um, we can do that again?” Josephine laughed. “No, because I’m not letting you go.” A grin spread over Crispin’s face, only to be suddenly tempered into a frown. “Jo,” he said. He still hadn’t let go of her. “Do you realize what you did today?” Josephine shook her head. “Not really, no. But I know that everyone finally saw me, and I finally saw you,” she said softly. Crispin’s eyes softened. “And what did you see?” He let go of her, and reached behind his back. Josephine felt a lump rise in her throat. “My best days start at the pool. Because that’s where you are. And they end here. Because it’s where you are.” Her voice had ended in a hoarse whisper. The strap of the guitar came undone, and Crispin wrapped his arms around her, the neck of the guitar gripped in one hand. His other hand tangled into her hair, and she wrapped her hands around his neck. Crispin finally raised his head, breathing hard. “So… we’ll have to do a lot more song writing then,” Crispin said. “Hours, I would think,” Josephine grinned.  About a year ago, I began this blog with a post about who Ada Lovelace was. Now, on another Ada Lovelace Day, I’d like to talk about who she wasn’t. A few months ago, I received a reply from an agent about my novel, The Steel Lady. Ada Lovelace is not the protagonist of the novel, but she is a prominent character. The agent was good enough to offer some feedback, but their main point was befuddling; they asked why Ada, “an influential feminist and historical figure,” had a life so fraught with conflict, particularly in relation to those close to her. The comment made my brain itch. On the one hand, I wanted to point out that Ada was categorically not a feminist, nor was she particularly influential. On the other hand, I bristled at the idea that personal conflict somehow negated feminism. Let me start by saying that I love all things Ada Lovelace (or Ada Byron, if you prefer). I love that she was the poet Byron’s daughter. I love that she was taught math in order to control her “passions”. I love that at age eighteen, when she met Charles Babbage, she immediately understood his Analytical Engine, the mechanical computer that was never built. She understood computers before computers existed. Compared to that, whether or not she really was the first computer programmer seems superfluous. In my novel, Ada Lovelace is a tragic character. She is bitter, addicted to gambling, in conflict with her husband, and fatally ill at the age of 36. This is the part that I didn’t make up. Ada’s own time did not allow her to fulfill her potential as a programmer and mathematician; even Charles Babbage, her mentor and collaborator, implied in his publication of her Notes that it was not in fact Ada’s work, but rather his. Even her death by uterine cancer smacks of an unfairness to her as a woman. I understand the desire for a compelling feminist heroine. The difference is that when I went looking for one, I didn’t find Ada. I found her daughter. Both in my novel and in reality, there was hope for Annabella King (later Anne Blunt) in a way that there wasn’t for Ada. The world was changing in a way that allowed for choices for woman that, though still unfair, were at least more liberating. History doesn’t cast Ada in the light of an influential feminist figure – she achieved little and died young. For many years, her achievements were nearly forgotten. She makes a much better feminist rallying cry. Her story may not influence you, but it should make you angry – for her, and for women like her whose potential is consistently wasted because they are women. The more I think about the comment, the more what bothers me is the implication that somehow a woman can’t be both a feminist and a conflicted character. It seems to imply that Ada’s flaws are incompatible with her supposed influence. Ada's intelligence was unfulfilled; if the gambling and affairs at the end of her life can be attributed to anything, they ought to be attributed to that. She struggled and failed. If we pretend otherwise, we do a disservice to her, and to women everywhere who struggle against insurmountable odds. If we ignore these failures, we gloss over the very injustices that gave rise to feminism in the first place. If we’re going to remember Ada Lovelace today (and we should), then we should remember all of her. If we wish to recast Ada Lovelace as a feminist figure, it ought to be by letting her be as human as the next man. This post was going to be about Shakespeare. Then Rick and Morty aired their last episode for Season 3.

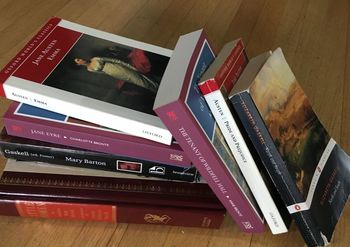

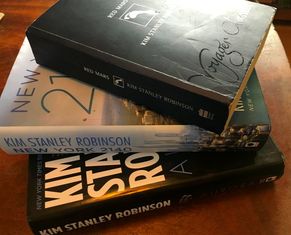

So yeah. Now this is going to be a post about Shakespeare and Rick and Morty. Because apparently, my brain is made of silly putty. The last episode of Rick and Morty Season 3 was unsatisfying. It’s okay, you’re allowed to agree. It doesn’t make you a bad Rick and Morty-ite. It was unsatisfying for all the reasons a show is unsatisfying. The action sequence was too long. The stakes of the story were difficult to keep track of. The characters were occasionally mildly, occasionally wildly, out of character. And the ending, by Rick and Morty standards, was pabulum. A glossed over, almost-laugh-track ending with Rick frowning at a weirdly happy Smith family. What annoyed me most wasn’t actually the last episode. It was the reviews of the episode. It was the casual assumption that everything in the last episode should be taken at face value. That Beth and Jerry really have chosen to get back together, that Summer really does have a suddenly connected relationship with her mom, and that Morty, somehow, chooses a simplified lie as his life. A reviewer commented that the Smith family has chosen escapism over Rick’s universe; the very “unrealness” of it suggests that it isn’t escapism, it’s temporary. Maybe Beth is a clone. Hell, maybe they’re all clones. Either way, the delightful bliss isn’t going to last, so why pretend this is some moral awakening for Rick’s character? One reviewer commented that Rick had been “returned to the ground” by this episode. What? The ground of what planet? Season 3 showed, time and again, that Rick’s intelligence often comes in the form of being a devastating curse. What it did not show was Rick being wrong. Sure, maybe that can last into the credits of the last episode, but I wouldn’t give that premise thirty seconds in the next season. Which brings me to Shakespeare. This summer, I watched a production of The Merchant of Venice at Vancouver’s Bard on the Beach. I do not love The Merchant of Venice, but I do love Bard on the Beach, and their dedication to performing every one of Shakespeare’s plays, no matter how terrible. I was expecting The Merchant of Venice to be mediocre at best, not because of production, but because of the script. It was outstanding. The problematic parts of The Merchant of Venice were not glossed or ignored – they were embraced. Instead of pretending that the play is a comedy with an occasional dark moment, the play was filled with sleazy, arrogant characters who are cruel to each other. It might seem that such a portrayal would render us unsympathetic to the pain and trials of those characters. It didn’t. It drove home the inhumanity of the entire piece, and the fact that Shakespeare and his society held beliefs we would find unforgivable. Sometimes a writer that you love is terrible. Sometimes a character who is reprehensible is the one that you empathize with most. Why lie about either one? When we gloss over what is problematic, we fall into the same trap as the Smith family – a delusion that at best can only be temporary. With the exception of the last episode, Season 3 of Rick and Morty was devastatingly good. It was dark, emotionally in-depth, well-paced, and hilarious. Reviews of the finale that talk about “resetting” and “starting from scratch” ignore the complete impossibility of actually doing that. Rick can’t. Much as he might try to, Morty can’t. And be honest – after the emotion pangs of Season 3, you as the audience member can’t. Let’s hope that, as usual, we’re being messed with, and that the season isn’t quite done.  This is not a pile of women's fiction. It is a pile of books. This is not a pile of women's fiction. It is a pile of books. I have been querying agents and publishers about my novel, The Steel Lady, and I have come across a category that makes me scratch my head – women’s fiction. It is usually given within a long list of other genres – young adult, science fiction, mystery, fantasy – that the person in question will consider. It made me think of when I was about sixteen, and I was visiting my grandma. My dad came in to borrow a book – a novel by Georgette Heyer, who wrote romances set in the Regency. When he left, my grandma made a derisive sound, and when I asked what the problem was she said, succinctly, “I don’t understand it. Those are women’s books.” It’s one thing for someone raised three generations ago to hold that opinion, but it seems problematic that the category remains intact within the publishing industry. The aggravating thing about it is that whenever I see an agent or publisher who accepts women’s fiction, I’m caught between delight and annoyance. I’m fairly certain that my novel falls well within the parameters of women’s fiction, as it has a female protagonist, and focuses on her development, growth, and relationships. It is a troubling assumption to stamp this kind of fiction as purely of interest to women. Let’s look at two examples of fiction that have stood the test of time: David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens, and Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Bronte. Jane Eyre is easy to label as women’s fiction. It charts the development of the young woman in its title, and a sizable amount of the novel focuses on the love story between Jane and Mr. Rochester. So then, is David Copperfield… men’s fiction? It focuses on the growth and development of a male protagonist, but no one would think to categorize David Copperfield as anything as pejorative as “men’s fiction,” even if such a term existed. I am no less guilty of this than anyone else. When I have assigned the Classics Project to my students, and they ask which book they should read from my list of suggestions, I have in the past recommended Lord of the Rings, Dune, and Dracula to the boys, and Jane Eyre, North and South, and Pride and Prejudice to the girls. This is ridiculous and needs to stop. All the books on the list are ones that I have read and loved, because they are wonderful, engaging books. The gender of the protagonist was irrelevant to me, and is equally irrelevant to my students. Then there are the novels that would seem to be women’s fiction, that aren’t. In my own novel, the story is not simply that of one young woman’s life, but also the story of enormous technological upheaval and change. As soon as it includes speculative elements, does it cease to be women’s fiction? This seems odd, particularly since genre fiction is so often where the strongest female characters are to be found. For example, does The Hunger Games count as women's fiction? It has a female protagonist. What about Marissa Meyer’s Lunar Chronicles? They, like Jane Eyre, are even named after their female characters. How about James S.A. Corey’s Caliban’s War? Two of its character narrators are Chrisjen Avasarala and Bobbie Draper, pretty much two of the toughest women in fiction. Why are these not pigeonholed as “women’s fiction”? A term like women’s fiction excludes in both directions. It excludes in what it leaves out – science fiction, dystopian fiction, fantasy, mystery – and in who it leaves out – namely, men. If women should read David Copperfield (and they should, by the way), then men should also read Jane Eyre. There is a wonderful and wide selection of fiction that includes female voices, but it is not enough for these voices to only be heard by women. It is imperative that women read stories of men, and that men read stories of women, and that we all read stories because move us and entertain us. Our stories are how we create empathy, and it does us little good to only empathize with our own side.  When Three Square Market, a Wisconsin vending machine company, announced this week that it would offer microchip implants to its employees, the reactions ranged, understandably, from delight to panic. Some hailed the next wonderful step of the computer age, while others predicted the coming onslaught of our robot overlords. There is legitimate enthusiasm over the increasingly science-fiction-like places that technology might take us, and legitimate concern over the ugly path it might lead us down. It seems to me that a question that is less addressed is not what technology we develop, but who develops it for us. Kim Stanley Robinson, the author of Aurora and New York 2140, recently commented that “we live in a present mixed with various futures overshadowing us. In essence, we live in a science fiction novel we all write together.” It’s an almost optimistic idea, but nowhere does Robinson suggest that we all have an equal hand in the writing. Rather, our world looks to be on the path of Robinson’s Mars trilogy, where large corporations have a major say in the exploration and exploitation of the Red Planet, sometimes to the detriment of the inhabitants of both Earth and Mars. In writing the future, we can often forget to ask who does the writing. Three Square Market is not the only example. The man who seems most poised to be Robinson’s fiction made real is Elon Musk. We stand in awe as he advocates for exploration and colonization of Mars, for the preservation of this planet through alternate energy, and more recently, for the development of brain implants to treat serious diseases. Much as I admire Musk’s goals, it is worth remembering that he is not a saviour. He is the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, and however noble his intentions, his position as head of two corporations comes with strings. We cannot, as citizens, simply accept that human development and innovation comes solely from corporations designed not for our benefit, but for our consumption. In every field – from nanotechnology to space exploration – there is a profit motive, and so there must also be an active participation from governments to ensure that it is not merely the interests of corporations that are served. To his credit, Musk seems to know this. He actively seeks the investment of governments in his proposed plans for Mars, because governments are the only one who can assemble the kind of capital that such a plan requires. They can assemble it because they serve a large group of citizens, who ultimately get some say in their expenditures. Government participation and regulation does not come from a vacuum. It requires citizens who are sufficiently aware of the implications of developing technology to demand that their governments have a say over how those technologies get used. It demands, frankly, more work from all of us, both to learn the technical underpinnings that we are permitting, and to debate how far we will permit them. It demands that we bother to participate in government process, because we will not be permitted to have our voices heard in a corporate boardroom. Some will say that this is a fight that we have already lost. That corporations will advance their goals and technologies unchecked by the needs of humanity. I contend that we have not yet encountered that fight, possibly because we are still too delighted by the spectacle that such innovation gives us. We are no different from the Victorians wandering through the Great Exhibition of 1851, marveling at the heavy industry that was to improve every echelon of life, without calculating its cost. We have no excuse to be so naïve. Writing science fiction, true, good science fiction, requires on some level knowing science fact. If we are to be the writers of the science fiction novel in which we live, we first need to understand the world from which we write. Given that we have access to the largest and most accessible repository of knowledge that the world has ever known, we have a good place to start.  It’s summer, and with summer comes my hardwired need to go camping. For me it seems required, but it’s hard to convince a non-camper of the virtues of camping. It’s easy to see why. You’re opting to sleep on the ground over sleeping in the perfectly good bed that you already have. There are bugs, and there is dirt. If you head back-country camping, as my family did when I was young, you have no electricity, no electronics, and often no source of water that you don’t sterilize yourself. How is this a holiday? I whined about enough camping trips as a teenager to understand this view; now, my instinct is simply to counter that it is a holiday because of all these things, not in spite of them. You have dirt under your nails, you’ve been wearing the same t-shirt for three days, and your hair is raked back into sunscreen smeared braids – and nobody cares. Instead of electronics, you amuse yourself by watching seeds from a cotton tree waft upwards in the heat of a campfire. Camping is amazing and liberating and relaxing, even when you’re working. It connects you with a world that is alive and vitally important. It’s a privilege to be able to do it. The problem is, for many people, these arguments are weak. This is where this post becomes less about camping, and more about writing. Because with camping as with writing, it isn’t the big things that make it meaningful – it’s the little things. I tell my students, when they are writing, that specific is better than general. In arguing in favour of what I can’t explain, I’m going to follow my own advice, and give specifics. I love the practicalities of camping. I love campfires: everything about them. I love the smell, the sound, and the light, and I love the memory of shooting water pistols against the side of their iron grates when I was little, just to hear them sizzle. I love making the best possible eggs that I can on a two-burner propane stove (fried in bacon grease, of course). I love dusk in a campsite, when it isn’t quite dark, and you push your night vision a little longer so you won’t have to turn a lantern on. Not quite yet. The outdoors has educated me my whole life. My family hiked into the alpine of Black Tusk when I was five; in the morning, I was confused as to why there was heavy frost on the ground in August, and got my first lesson on how elevation affects temperature. It shows me animals and plants up close – sometimes heart-stoppingly close, like the time we went canoeing in the Bowron Lakes, and came through the rushes to see a massive mother moose and her calf. It lets me share what it has taught me with my students when I take them camping, like the fact that if you stroke a slug, you can pick up sticks by touching them with its slime. It’s small moments and shared memories that make this strange activity wonderful. As with any story, the meaning is in the details, and the details are virtually endless. I invite you to add your own below. Happy camping.  Last week, a Martian character from SyFy’s The Expanse looked out on the ocean of Earth and said “You take it for granted,” while the news filled with changes to government policies on climate change. Cruel coincidence. Though if it is, it feels strangely expected. My love of science fiction predates my love of science. Both are speaking to me this week, as I read Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot, and as I watch the second season of The Expanse, an adaptation of the novels of James S. A. Corey. It strikes me that they share something in their tone. This seems, on the face of it, unlikely; Carl Sagan is an unfailing optimist towards human endeavours in science, and The Expanse, for all its glory, is pushing towards dystopian in its portrayal of Earth. Yet the message that they share, the message that Sagan never stopped preaching, is that Earth is precious. Or to quote The Expanse’s Amos, “You can’t replace Earth.” It seems that this should be otherwise, at least in fiction. With powerful fusion drives, with mirrors that concentrate Jupiter’s light onto its moons, with domes and terraforming on Mars, surely there is some distant day when we will not rely on the Earth? The Expanse says no. Sagan says no. Physics and biology say no. Going to Mars, and even terraforming it, is within our capabilities, but a terraformed Mars is not a substitute for Earth. And even if the planets of our Solar System are possible, the stars are not; the distances in our galaxy are insurmountably vast. The ability to find or build a new home for humanity is so close to impossible that it’s a rounding error. The difficulty of even leaving Earth, never mind replacing it, comes home when I’m teaching the laws of motion to my students. My repeated line is “Physics is not your friend.” As they try to imagine spacecraft that might actually leave the Earth on trips to the Solar System, they are not allowed to skip the details. The incredible challenges of leaving Earth are reinforced even as they try to work around them. Ironically, this is not rocket science. It is basic arithmetic. It does not take long for students in my class to realize that even modest outings into space are extremely difficult. The lesson is not merely Newton’s laws, but the reality that they reinforce: space travel is hard. Earth is all the more precious because of it. That we forget this for even an instance, that we take those oceans for granted, is inexcusable. That governments forget this is borderline criminal. I could expound on the environmental catastrophe inherent in ignoring our tenuous place in the Solar System, but better scientific minds than mine have already done so. What I object to is ignorance, or the stubborn refusal to see facts that is currently masquerading as ignorance. It is immoral for governments to act as if the Earth is expendable – tantamount to burning down a house with the inhabitants still inside. As always, Carl Sagan said it best: “Like it or not, for the moment Earth is where we make our stand.” For the moment. Moments in the span of cosmic time are long – longer than any of us may have. For the moment, this is all we have – a blue dot suspended in the vast expanse. |

Author

Jane Perrella. Teacher, writer. Expert knitter. Enthusiast of medieval swordplay, tea, Shakespeare, and Batman. Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed